Upcoming Screenings:

no event

Follow us on Facebook

HELP BRING FINDING KUKAN TO CLASSROOMS

Sign up for our mailing list.

Category Archives: Asian American History

The Power of the Press: Part 1– May Day Lo

A blog in support of FINDING KUKAN’s 10K in 10weeks “Keep This Film Alive Campaign”.

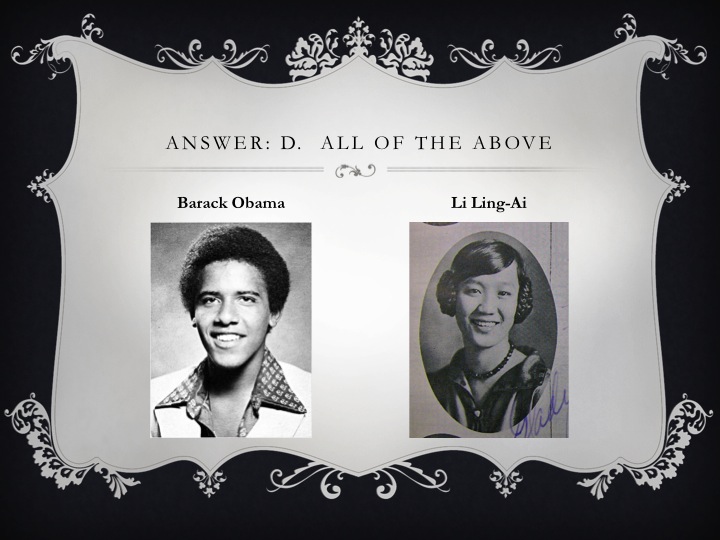

In the Lily Wu detective novels by Juanita Sheridan one of the colorful sidekicks is a female reporter named Steve (Stephanie Dugan) who funnels information to her two amateur detective friends Lily and Janice. Since many of her fictional characters are based on real life people, I wondered if Sheridan based Steve on some of the ballsy female reporters who were breaking into newsrooms in the 1930s. So my ears pricked when I heard that Li Ling-Ai had a journalist friend in the 30s and 40s named May Day Lo. Yes, that is her real name, and no she was not even born in May.

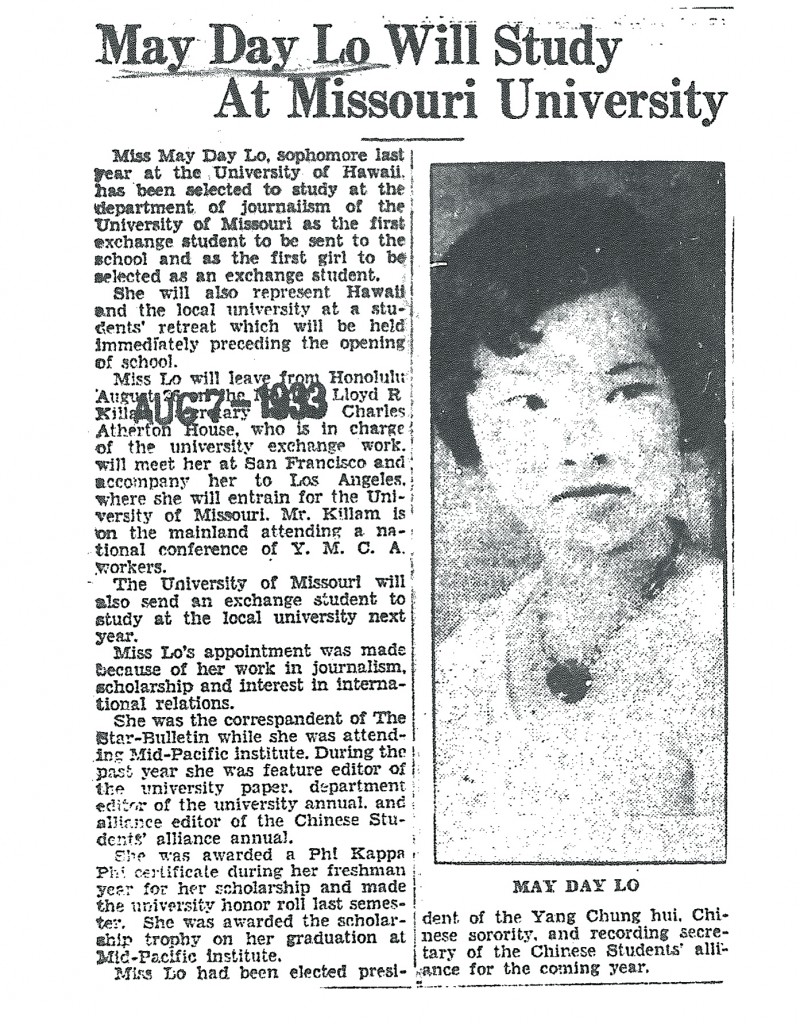

May Day Lo at the University of Missouri (photo courtesy Susan Cummings)

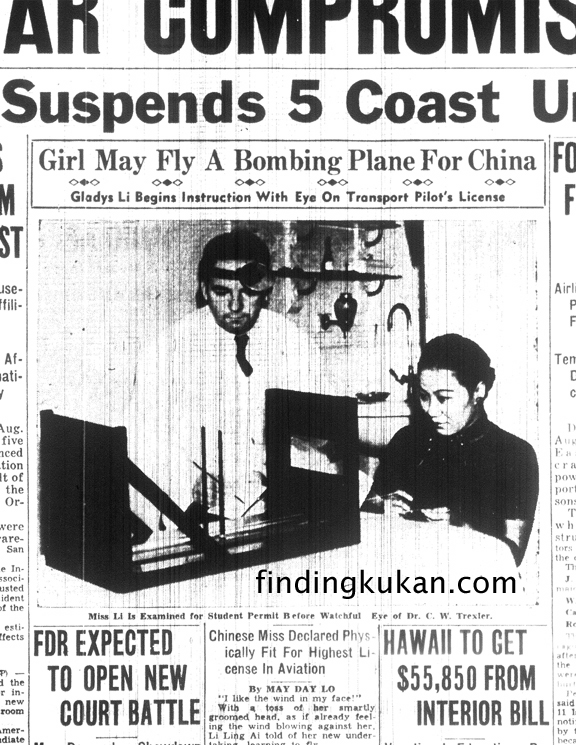

In the mid 1930s May Day Lo made history by being one of the first Asian American women hired to report for a major daily newspaper. The progressive Honolulu Star-Bulletin hired Lo and Ah Jook Ku after they graduated from the University of Missouri Journalism School. May Day Lo also broke ground at Journalism School by being the first “exchange student” accepted there (remember, Hawaii was still a territory and not officially part of the United States).

Notably, in 2010 when the Asian American Journalists Association put together a list of pioneering Asian journalists, a majority of them were from Hawaii. AAJA historian Chris Chow commented, “Hawaii was more open to multiculturalism. There was recognition that this is an important market and you’d better well serve them (Asian-Americans) if you want to make any money.”

Back in the 30’s, the Star Bulletin seemed to cover stories about local Asians more comprehensively than the rival Honolulu Advertiser. And May Day Lo’s byline was on several early articles written about Li Ling-Ai, including the one that probably prompted Advertiser reporter Rey Scott to call Li Ling-Ai into his office for an interview on that fateful night in 1937 when plans for making KUKAN were first hatched.

Reporter May Day Lo gives front page coverage to fellow Chinese American pioneer — Li Ling-Ai (aka Gladys Li)

I love knowing that a petite Chinese woman who was raised by a reverend in Hilo was the first exchange student at the prestigious University of Missouri School of Journalism and that the power of her pen brought attention to another pioneering Chinese young woman in a way that changed her life forever. I wanted to find out more about May Day Lo, especially when I found an intriguing letter from her to Li Ling-Ai:

July 31, 1941,

Dear Li Ling Ai,

Now that I am home again, it all seems like a dream that I met you and all the others in New York and had such a wonderful time…. Please give my Aloha to Mrs. James Young, Rey Scott and Mr. Ripley when you see them.

May Day Lo had been in New York right around the time when KUKAN premiered at the World Theater just off Broadway! She had met both Rey Scott and Robert Ripley – two key players in Li Ling-Ai’s life at the time. Could May Day hold clues to some of the unsolved mysteries surrounding KUKAN?

Unfortunately May Day had died in a tragic car accident in 1986. May Lee Chung, editor of the ACUW publication that documents so many pioneering Chinese women’s lives (see other posts about this “Orange Bible”), could remember clearly the circumstances of May Day’s death. But she did not know what had become of May Day’s only child David, someone who might be able to tell me more. The trail remained cold until the Power of the Press struck again in 2011. Stay tuned…

Support our 10K in 10 Weeks campaign by clicking the red button.

(As of 9/6/13 we have raised $5,025 and have $4,975 more to raise by 10/15/13)

Soo Yong – Another Chinese Woman We Should Know More About – Part 2

A blog in support of FINDING KUKAN’s 10K in 10weeks “Keep This Film Alive Campaign”.

A family story often told about Soo Yong (born Ahee Young) is that when she was four or five years old her father became gravely ill and summoned the family to hear his last words. But Ahee was missing. The family searched all over for her. They finally found her in Wailuku town. She was completely mesmerized by the performance of a Chinese opera troupe who had come to town. This is Soo Yong’s earliest dramatic memory.

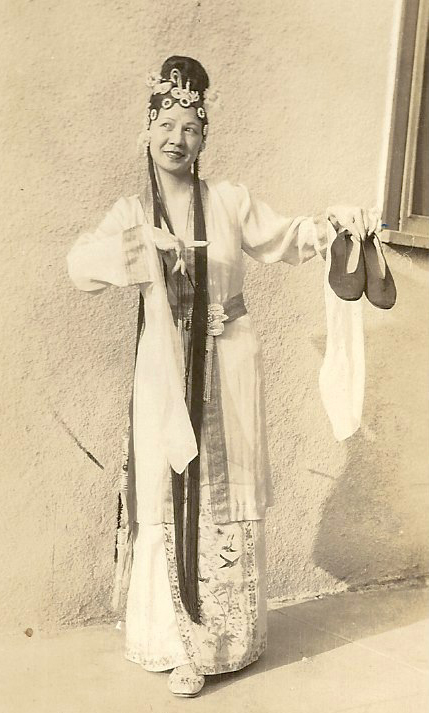

Chinese Opera Performers in Hawaii

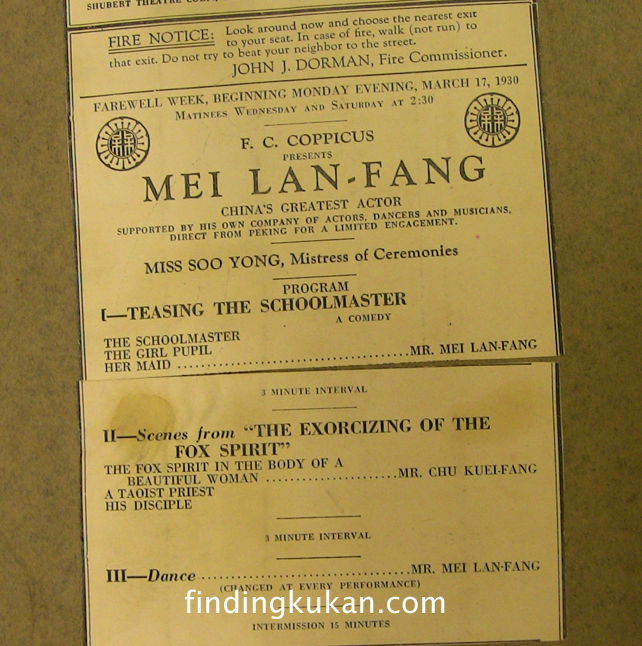

Si it must have been a dream come true for Soo Yong when in 1930, at 28 years of age, she was chosen to accompany the most famous Chinese opera star of all time on a six-month tour of America.

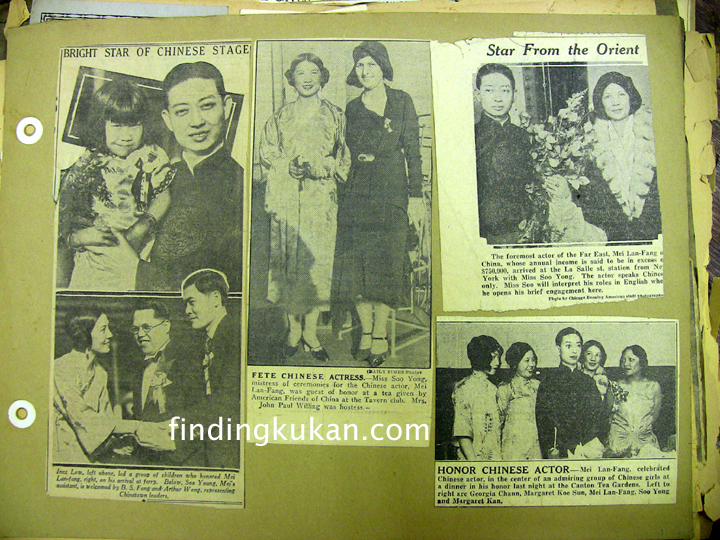

Soo Yong acts as Mistress of Ceremonies for Mei Lanfang’s 1930 tour of America

Mei Lanfang was also idolized by Li Ling-Ai whose dramatic interests were stirred up by Chinese opera performances her father took her to when she was a young girl. During his 1930 tour Mei stopped in Honolulu and Li Ling-Ai had a chance to meet him.

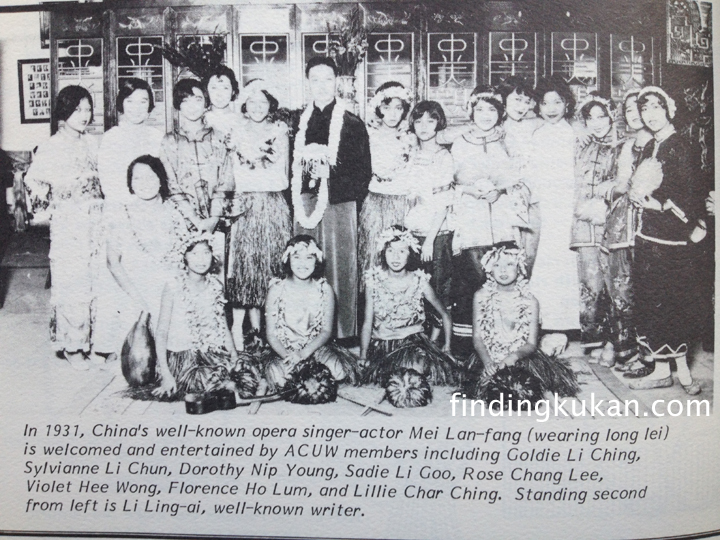

Photo from the ACUW publication TRADITIONS FOR LIVING

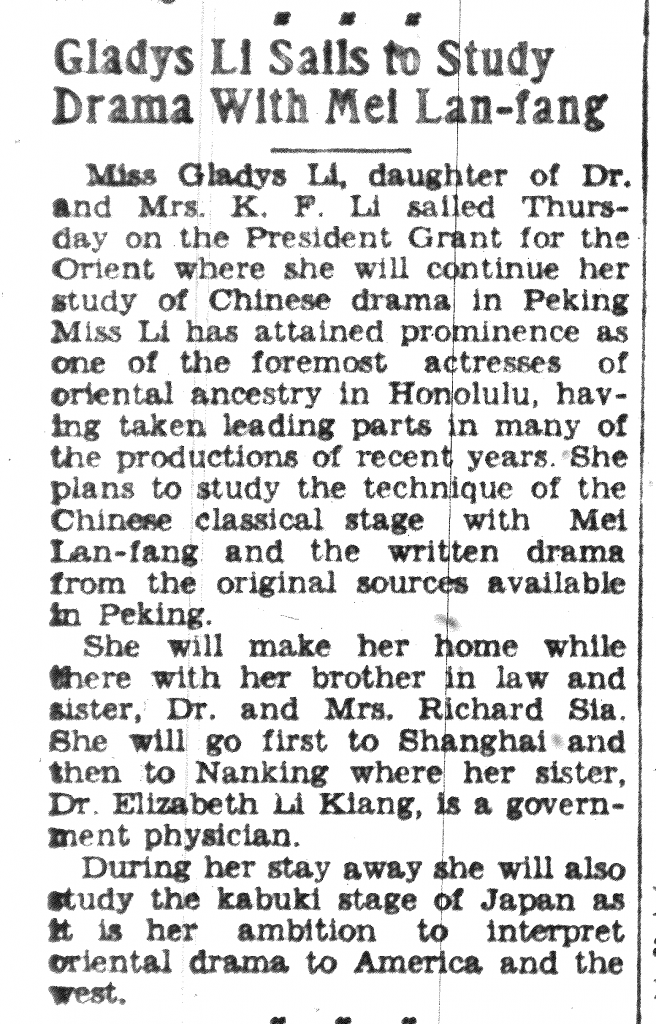

A year or so later Li Ling-Ai left on her second trip to China and told newspaper reporters she intended to study with the great man – a lofty goal for a recent graduate of the University of Hawaii. I wondered if Soo Yong’s insider position emboldened Li Ling-Ai to approach the great Mei for lessons.

Honolulu Star Bulletin Article from August 6, 1932

I found no subsequent mention of Li Ling-Ai studying with Mei Lanfang. But several biographies of Li state that she studied privately with the famous dancer Chu Kuei Fang. It was hard to find any mention of Chu Kuei Fang on the internet and I began to doubt Li Ling-Ai’s claims. But in Soo Yong’s personal scrapbook that was donated to the University of Hawaii, I discovered Chu listed as a performer in a 1930 program for Mei Lanfang’s tour.

Chu Kue-Fang performs on the same program as Mei Lanfang

Chu must have been very accomplished to share stage time with the great Mei Lanfang. I wonder if this old photo, found amongst Li Ling-Ai’s possessions, is of Chu Kuei Fang. If anyone can positively identify the man in the photo, please let me know.

Could the man behind Li Ling-Ai be Chu Kuei-Fang?

Soo Yong and Li Ling-Ai also shared a passion for helping their Chinese homeland during the Japanese invasion of the country. As early as 1937 Soo Yong was performing in benefits to aid Chinese refugees.

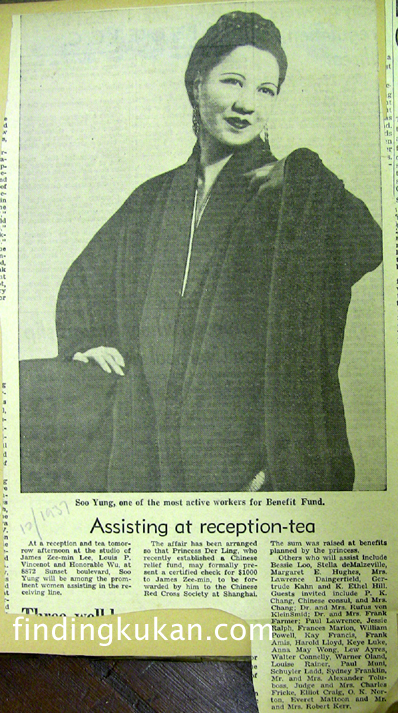

December 1937 Soo Yong hosts tea for China Relief

1937 was also the year that Li Ling-Ai sent Rey Scott to China so that the story of the people of China could be told in photographs and film – the film would eventually become KUKAN. Whether Soo Yong was a role model for Li Ling-Ai or simply another extraordinary Chinese woman who became a political activist when war came we might never know. But one thing’s for certain — we should definitely know more about her than we do.

Soo Yong: Another Chinese Woman We Should Know More About — Part I

Could the Chinese American actress Soo Yong have been an inspiration for the fictional Lily Wu? (photo courtesy of Barbara Wong)

I’m starting a 10-week blog-a-thon in support of our 10K in 10weeks “Keep This Film Alive Campaign”. The goal: get us back into the edit room on October 15 to finish a rough cut of FINDING KUKAN. What better way to kick off that effort than to re-visit my search for LILY WU – the fictional detective created by author Juanita Sheridan. According to Lily’s friend and Watson-like companion Janice Cameron, “Lily is a chameleon. She can change effortlessly into whatever character the occasion requires…” Lily is also smarter, sexier and more worldly than most of the Caucasian characters she runs into.

This book, published by the Associated Chinese University Women of Hawaii, is a wonderful collection of short bios

While trying to locate the real life inspirations for Lily Wu I recall poring over what I now think of as THE ORANGE BIBLE (see photo above) and stopping short at the entry for Soo Yong. Why? Because Soo Yong was a Chinese movie star from Hawaii! She appeared glamorous and gutsy, running away from a restrictive small town life in Wailuku, Maui for the more cosmopolitan Honolulu where she put herself through school at the University of Hawaii and then Columbia University in NYC. She was just the kind of woman who might have inspired Juanita Sheridan to create Lily Wu. But my interest in Soo Yong tailed off when I discovered that Soo Yong had left Hawaii before Juanita Sheridan arrived there, making it unlikely that the two women were friends.

My interest in Soo Yong was re-ignited when Li Ling-Ai’s sole surviving sister mentioned that Ling-Ai had spent time in Hollywood and had been friendly with a Chinese actress from Maui. Sure enough, a keyword search through the Los Angeles Times brought up a 1936 article placing Soo Yong and Li Ling-Ai together in Hollywood:

“East is east and west is west, and the two of them met last Tuesday afternoon at Joine Alderman’s Salon. The east was personified by a lovely Chinese lady whose name and voice are poetry itself, Li Ling Ai. Clad in her native black satin robes, embroidered in gold and silver and shining colors, she told the forty or so debs who comprise the salon about her native country. … And her words about the beauties of Pekin and her studies in ancient philosophy were translated to the debs by another Chinese-robed lady, Soo Yung.”

The gossip column inaccurately assumed that Ling-Ai could not speak English and Soo Yong was there merely as a translator, but it whetted my appetite to learn more about Soo Yong. Could she have been a mentor or role model for Li Ling-Ai?

Clark Gable and Soo Yong in The China Seas

Being an old movie nut, one of the first things I did was rent one of the Clark Gable movies Soo Yong had been in, China Seas. Although the movie depicts most Chinese in stereotypical coolie roles, Soo Yong convincingly plays a high-brow Chinese aristocrat who out-classes Gable’s ex-girlfriend played by Jean Harlow. This small 1935 role would lead to Yong playing two parts in the 1937 hit The Good Earth. She was also Jack Soo’s mother in Flower Drum Song and had supporting roles in Soldier of Fortune with Clark Gable, Peking Express with Joseph Cotton, and Love is a Many Splendored Thing with Jennifer Jones. Why we don’t know much about her may be because she was never able to have a full-fledged Hollywood movie career.

In 1935 Soo Yong advised islanders that Asians have “A Chinaman’s Chance” of breaking into Hollywood.

In the 1930s Soo Yong was interviewed by Loui Leong Hop for the Honolulu Star-Bulletin:

“When asked about the possibility for local-born orientals to break into the talkies, she simply said, “A Chinese has a Chinaman’s Chance.” Explaining further on this point Miss Young stated that at present the Hollywood studios are name crazed. If there’s a production which required an oriental to play the part, the Hollywood producers would invariably select one of their more famous actors or actresses.”

Unfortunately not much has changed in Hollywood, and Asians still struggle to find starring roles on the big screen.

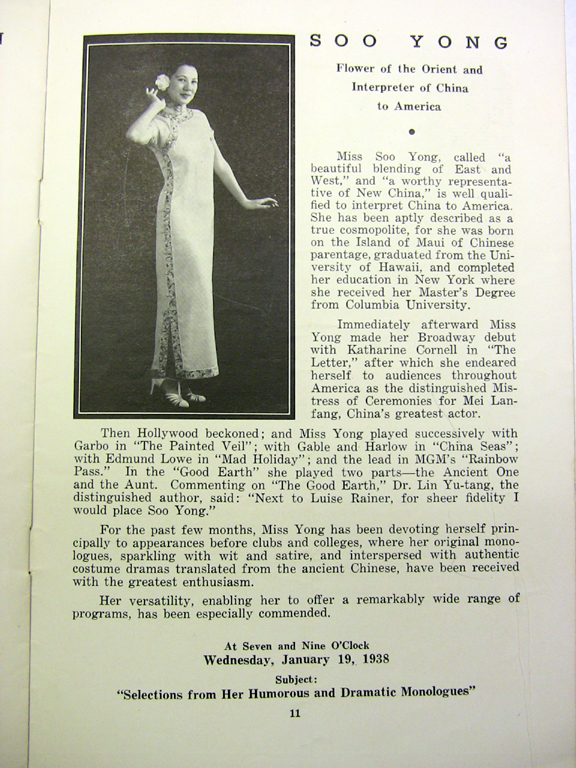

Soo Yong, Interpreter of China to America

Soo Yong would eventually make a living on the lecture circuit, performing entertaining Chinese monologues to educate audiences around the country about Chinese culture. As of this date Soo Yong does not even have a Wikipedia page, but we should definitely know more about this pioneering Chinese American actress. Stay tuned for part two of this blog where I’ll write about some amazing discoveries I found in Soo Yong’s personal scrapbook.

Support our 10K in 10 Weeks campaign by clicking the red button.

April 25, 2013 — Major Archival Discovery Starts with a Party

It was my husband Paul who convinced me that I should have a fundraising party. So last October I got many volunteers together to throw one. Terry Lehman Olival helped by sending press releases to the local media and got the attention of Star-Advertiser reporter Mike Gordon.

Mellanie Lee, Debra Zeleznick, Robin Lung and Terry Olival at “A Night in Old Shanghai” fundraiser

“That might be the coolest story I’ve heard in a long time,” Mike said, and promised to write an article on it. The more Mike found out, the more he wanted to know. His article grew and grew. My fundraising party came and went; my Kickstarter campaign came and went.

Finally the opus turned up – a 3‑page spread on the film, complete with color pictures, showed up in the Sunday newspaper and drew response from people as far away as Kentucky!

Mike Gordon’s article “Reel Obsession” appears in the November 18, 2012 Honolulu Star-Advertiser

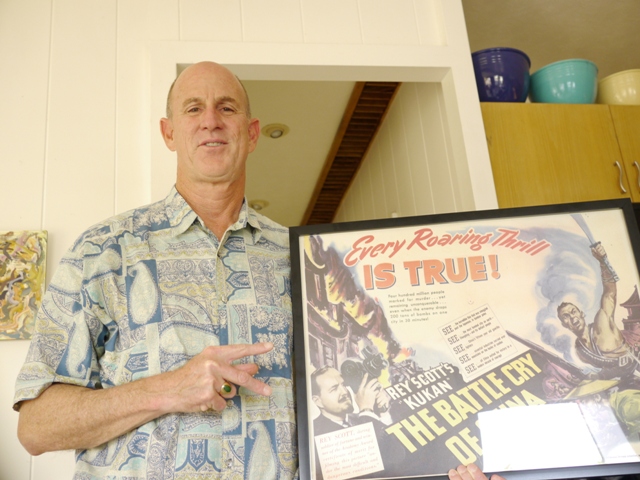

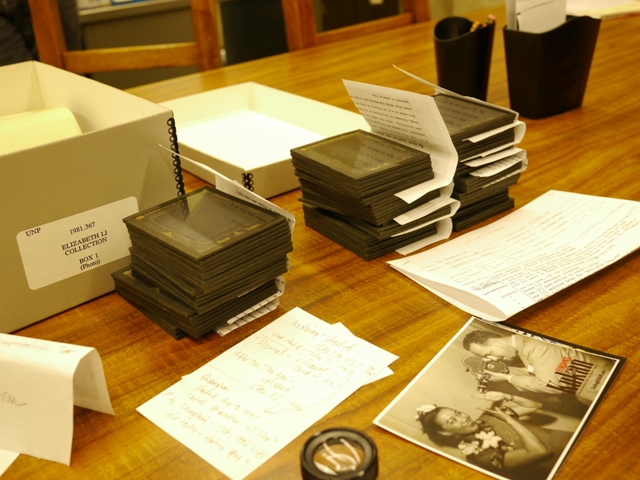

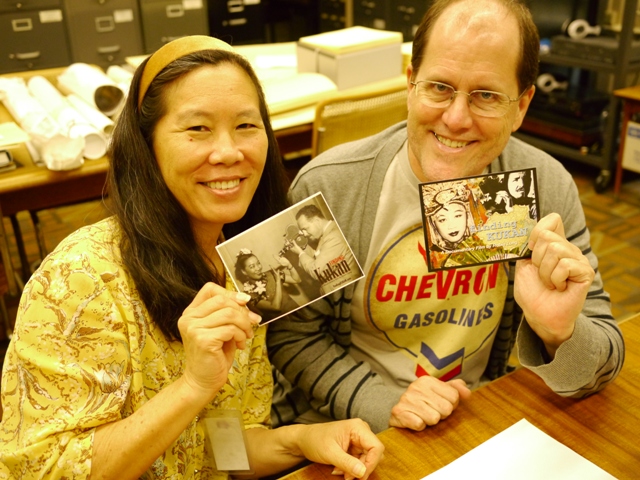

DeSoto Brown, curator at the Bishop Museum, also read Mike’s article and something clicked. He remembered a donation of lantern slides made to the museum by Betty Li, Li Ling-Ai’s older physician sister, back in the 80’s. In fact the slides were marked as being related to KUKAN! Early in my research I had read that KUKAN’s director Rey Scott lectured with a group of slides, but no one in his family remembered seeing them or hearing anything about them. I had given up on finding them.

So I was on pins and needles last week when I finally connected with DeSoto at the Bishop Museum and had a chance to examine the slides myself. They didn’t disappoint — 97 images of 1937 Nanking, including some with Rey and Betty Li, brought Rey’s first trip to China to life for me in a thrilling way and helped answer some of the mysteries that had been plaguing me for years.

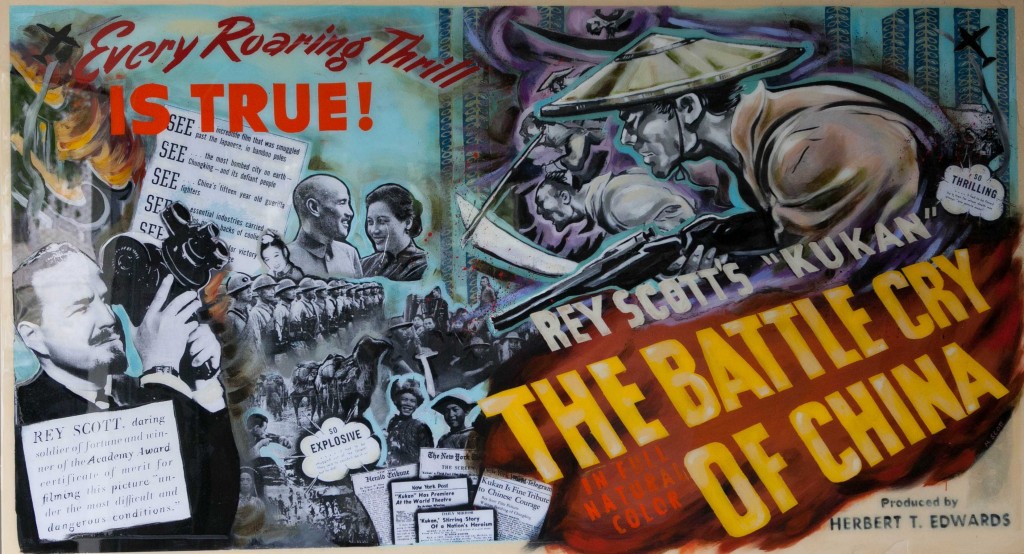

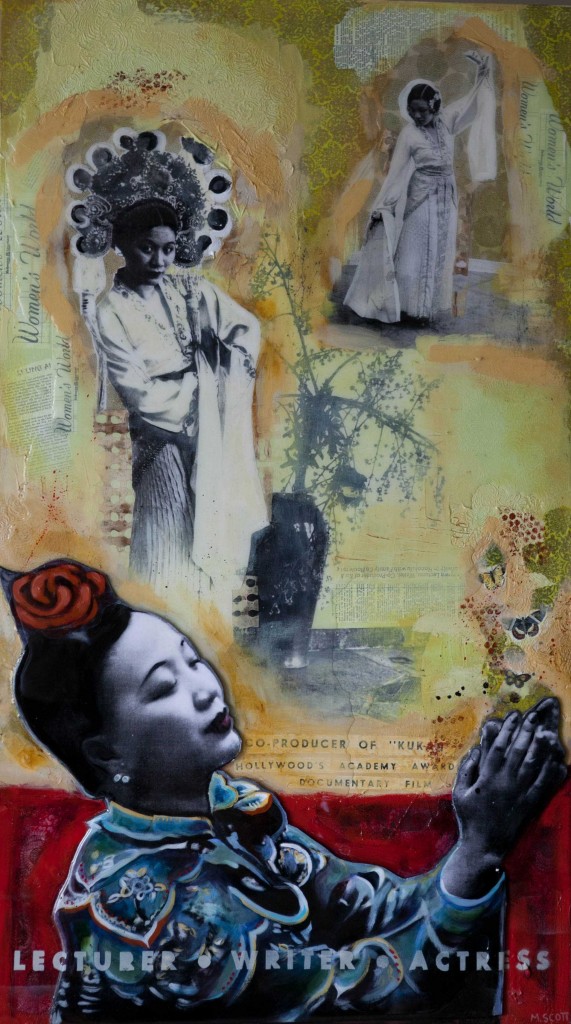

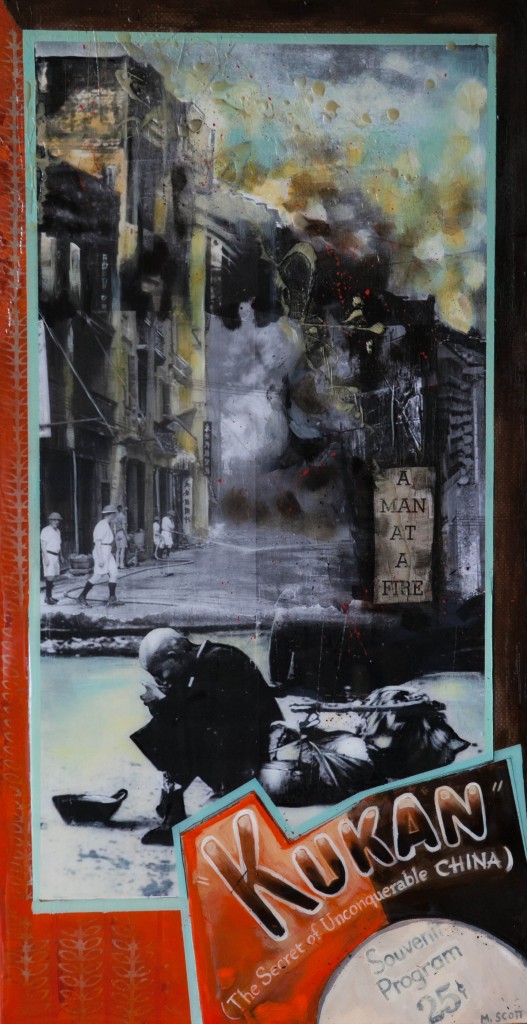

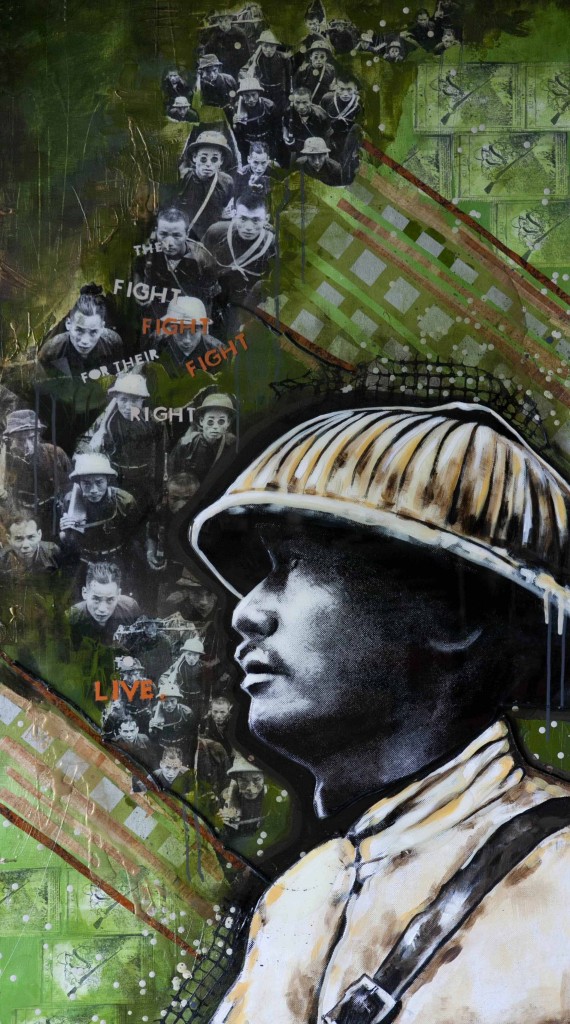

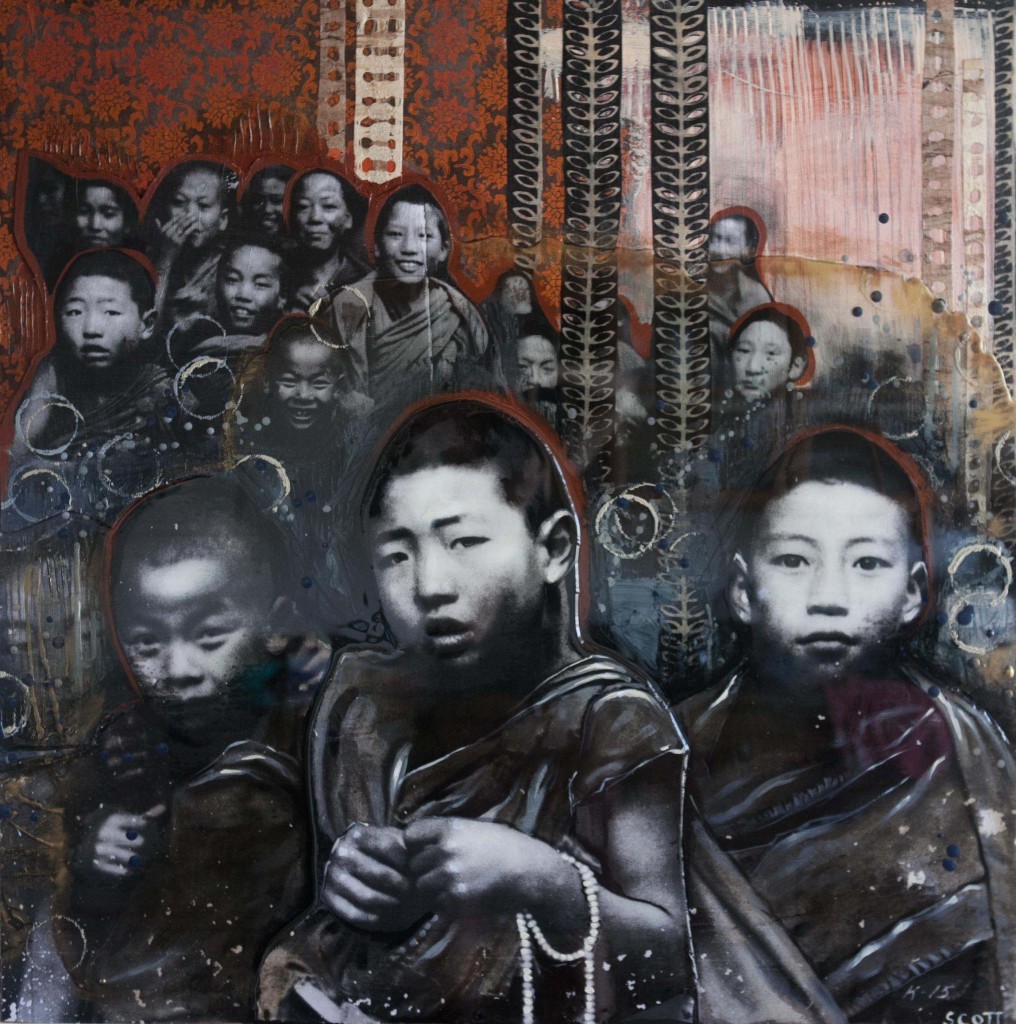

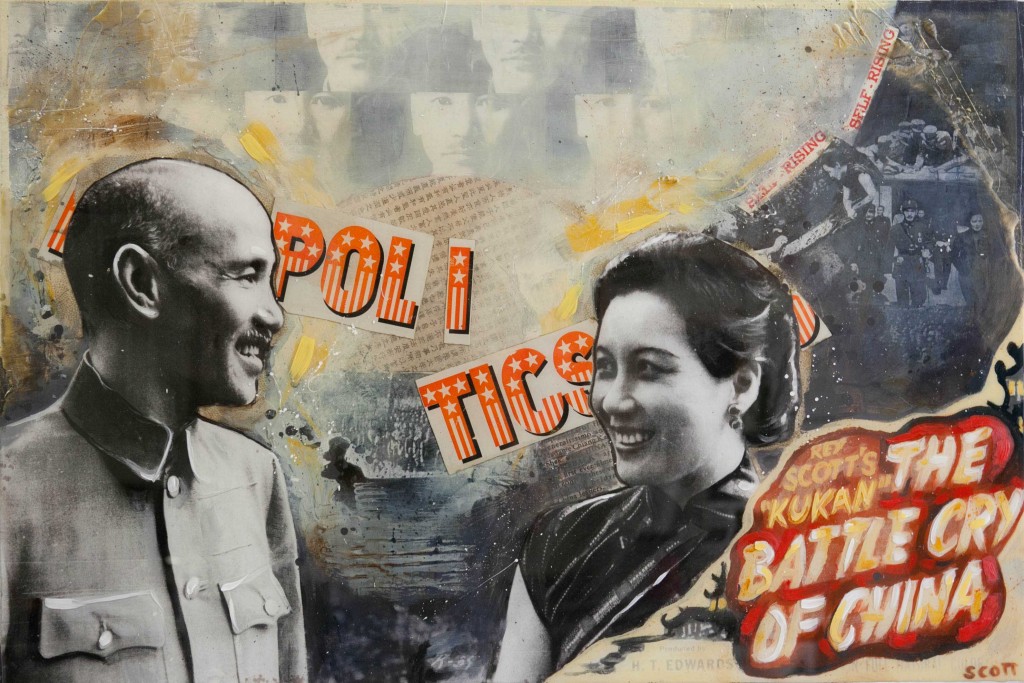

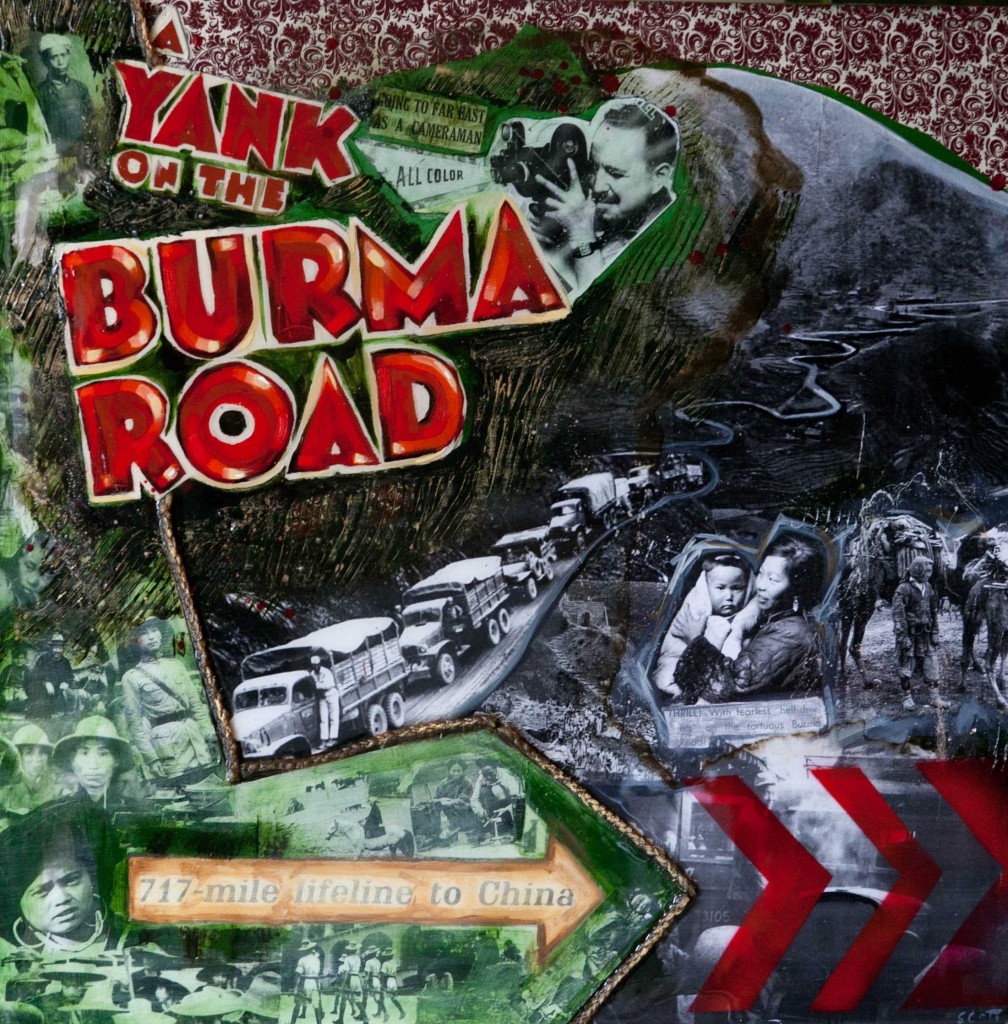

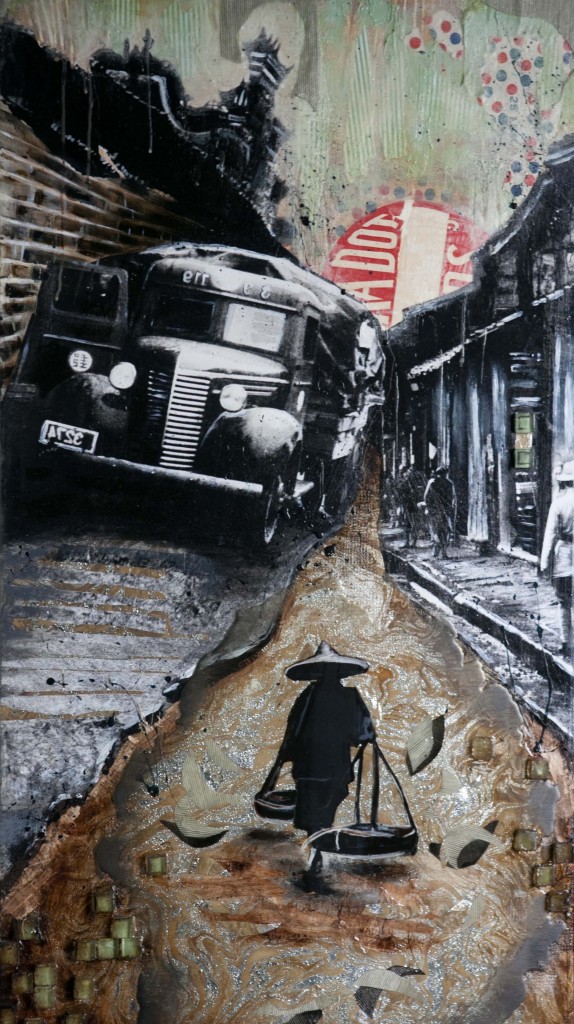

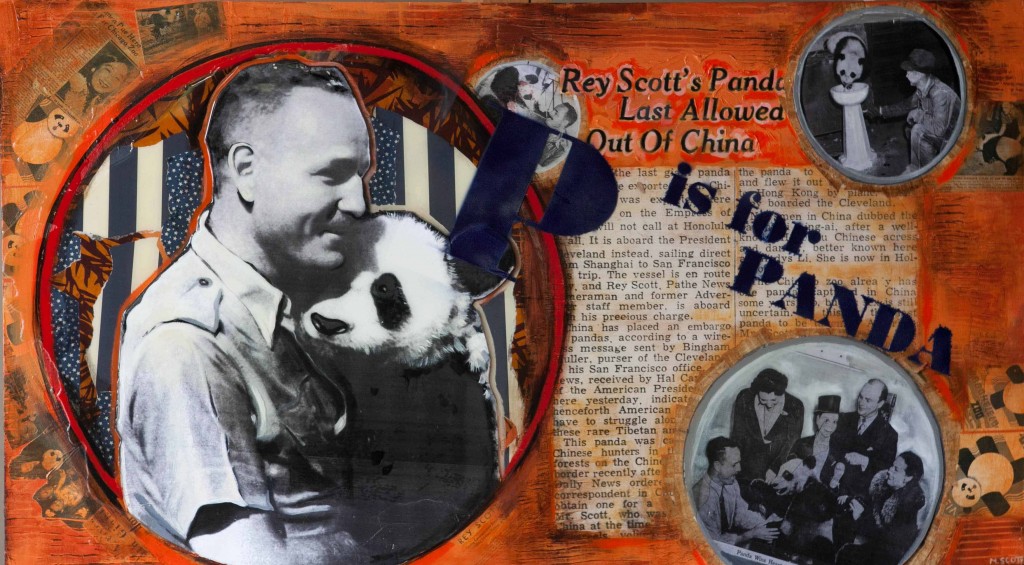

October 3, 2012 — Michelle Scott Delivers a Knock Out with her KUKAN SERIES

When I first made contact with Rey Scott’s granddaughter Michelle Scott and filled her in a little about the story behind KUKAN, she felt a need to transfer that story into paint and shared with me a vision she had for creating a whole room of paintings dedicated to her grandfather and KUKAN. It seemed like a far-fetched dream back then. So I was more than a little excited to go to Atlanta to witness the opening of Michelle’s solo show — THE KUKAN SERIES. Michelle hadn’t shared any images of the new work with me, so I wasn’t prepared for the visual sweep and emotional power of the work. It literally brought me to tears. Here are a few choice pieces from the show. WARNING — these photos do not do the pieces justice. The real pieces have an almost three-dimensional quality that allows the viewer to enter into the scene and experience a little of Rey Scott and Li Ling-Ai’s world back in the late 30’s.

Artist Michelle Scott with “Start of a Journey” the exclusive premium available for a $5,000 Kickstarter pledge (partially tax deductible).

The 36“X36” piece that Michelle created exclusively for our Kickstarter fundraising drive is displayed right in the front window of 2Rules Fine Art in Marietta. Casual strollers walking down the sidewalk can’t help but be pulled in to find out with the imagery is all about. For close up details of this painting go to our Kickstarter home page.

The KUKAN Series contains a few gorgeous tributes to Li Ling-Ai the Chinese American author who was the uncredited co-producer of KUKAN with Rey Scott.

The work below contains images of Li Ling-Ai from three different decades and three different locations (the old Honolulu Academy of Art, Beijing China, and New York City)

There are also fabulous pieces that provide a visual montage of the China witnessed through Rey Scott’s camera. He took both stills and 16mm color movies. Some of his old cameras are on display too with the original stills.

Rey Scott traveled all the way to Tibet and filmed some of the first color footage of prayer rituals there.

Michelle’s take on the original KUKAN lobby cards for the United Artists version of the film.

Rey Scott also filmed the famous Burma Road as it was being built.

A reminder of the British influence in Hong Kong which fell to the Japanese in 1941.

A whole movie could be made just about the baby giant panda bear that Rey Scott brought from Chengtu to the Chicago Zoo. Originally christened “Li Ling-Ai” by the foreing journalists in Chungking, it was later named Mei Lan when it was identified as a boy panda bear.

“Portrait of a Lady” and “For Him” are the first two pieces that Michelle Scott made in the KUKAN Series

There are many more gems in this show. But the emotional highlight for me was being able to see the first two portraits of Rey Scott and Li Ling-Ai that Michelle did. I first saw them on her website before we even knew each other and before she even knew who Ling-Ai was. This was the first time I was able to see them both in person. Since the pieces had been sold to different collectors several years ago, this was also the first time they were reunited in the same room for quite some time — a symbol of hope for me as I continue to seek funding to finish FINDING KUKAN.

If you are in the Atlanta area make an effort to see this historic show — up only until October 26, 2012

June 28, 2012 — A Visit to Yale and Chinese Exclusion

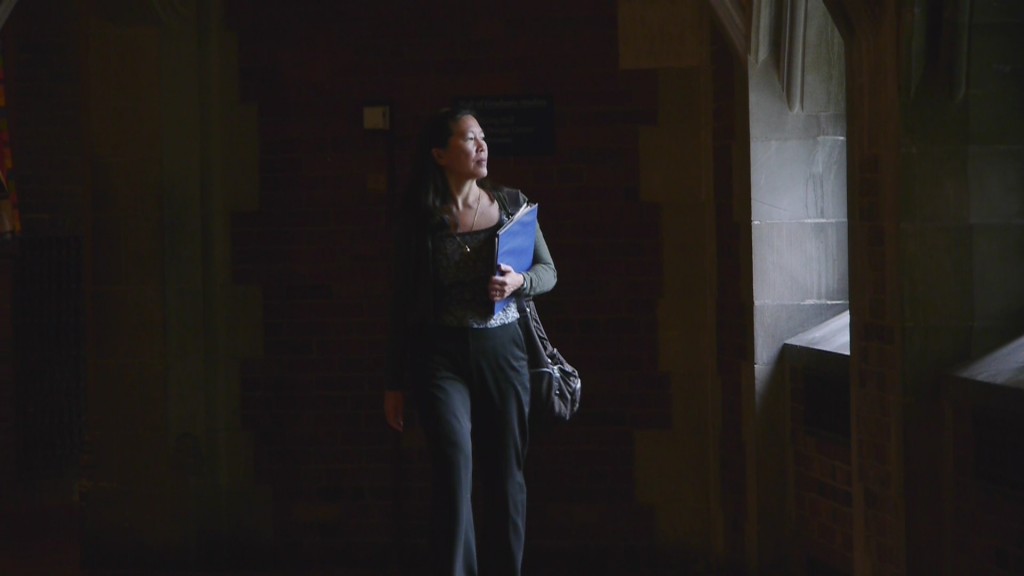

The recent FINDING KUKAN shoot at Yale University brought out the perpetual student in me. You can’t help but be awed by the vaulted ceilings and Knights of the Round Table atmosphere of the Hall of Graduate Studies where my interview with Yale Professor of American Studies Mary Lui took place.

The building reminds you how much history has come before you and how much you are ignorant of.

Fortunately the halls of learning at Yale are populated by people like Mary who dedicate their lives to gathering knowledge and disseminating it to people like me.

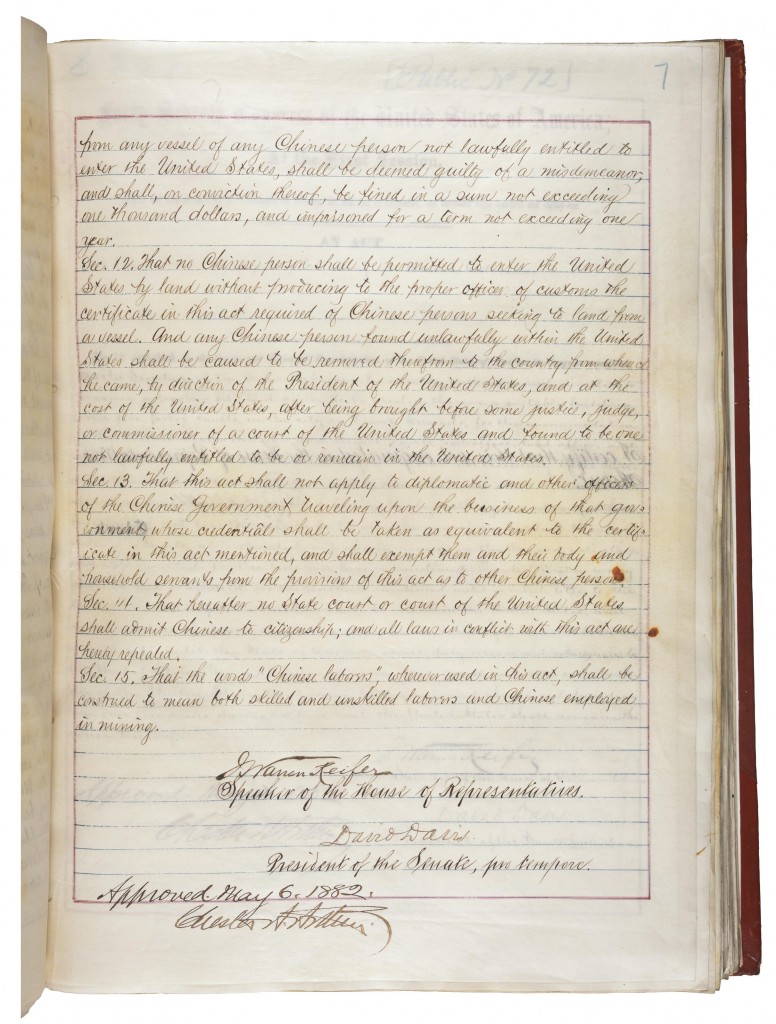

In trying to understand the social climate that prompted Li Ling-Ai and Rey Scott to risk money and life to make KUKAN, Mary Lui reminded me that the behavior of Chinese Americans like Li Ling-Ai was still governed in part by prejudicial immigration laws enacted against the Chinese — the most infamous one being the Chinese Exclusion Act passed in 1882.

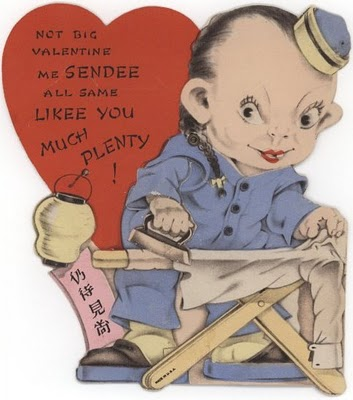

Meant to keep cheap labor from entering the US, the exclusion laws ended up doing much more than that. From restricting the formation of Chinese families, to rendering the few Chinese women around at the time exotic creatures with questionable backgrounds the Exclusion Laws had negative repercussions on even the richest and most educated Chinese Americans. It’s no wonder that with so few Chinese Americans around that stereotypes and misconceptions about them would form.

I came back to Hawaii much better prepared to appreciate the historic bill recently passed by Congress to officially apologize for the prejudicial laws that targeted Chinese and other Asians in America for over 80 years.

One of the stereotypes I had about my own ethnic background was that Chinese don’t make waves and passively accept their fate, letting bygones be bygones.

The courageous efforts of people like Congresswoman Judy Chu and organizations like the 1882 Project belie that stereotype and bring a new validation to the history of Asians in America that will hopefully prompt more stories about an era of exclusion that we still don’t know enough about.

Are there ways that exclusion laws have affected your life? Let us hear from you.