Upcoming Screenings:

no event

Follow us on Facebook

HELP BRING FINDING KUKAN TO CLASSROOMS

Sign up for our mailing list.

Tag Archives: Chinese American Women

November 29, 2014 — Year in Review (Part 2 — New York in June)

New York in June could only be made possible by the hospitality of longtime friend Peer Just. A free place to stay in New York meant that I could funnel some of our funds towards filming two crucial interviews with Asian American scholar Judy Wu and the award-winning author Danke Li. Both provided important insights into Li Ling-Ai’s motivations and how World War II transformed the everyday lives of women in both the United States and China. Answering the last-minute call for camera help were our New York go-to DP Frank Ayala and another longtime friend Ruth Bonomo.

Leaving NYC home base for a day of production on Long Island — first the subway, then the train, then the ferry.

Judy Wu, author of DR. MOM CHUNG, took time out from her Port Jefferson vacation to sit for a great interview. Ruth Bonomo pitched in as DP on short notice, providing wheels, camera and lights. Judy’s family fed us a great spaghetti dinner beachside. Signing K for KUKAN!

DP Frank Ayala with Danke Li, author of ECHOES OF CHONGQING, WOMEN IN WARTIME CHINA

A visit to New York also meant I got to hang out with Calamity Chang, who has volunteered to record temporary voice over lines that allow us to edit our historical scenes. Calamity constantly inspires me by her willingness to embrace her performance instincts and bare it all in her wonderfully tongue-in-cheek burlesque shows. She also knows her Chinese history and promotes projects like ours that bring it to the forefront. Her musician/photographer husband Mike Webb put in hours of free time as our sound man while dog Chewie quietly put up with our intrusion. After a super long recording session on a sunny Sunday afternoon, we all needed a New York specialty cocktail.

Going over scripts with Calamity Chang.

Musician and Photographer Mike Webb pitches in as sound man to record our temporary voice over tracks.

Chewie after a long recording session

One of the killer cocktails I had in NYC featuring cucumber and gin

Just being in NYC is a real shot in the arm for a filmmaker. Visual stimulation is everywhere and so are other artists whose very existence and work are like cheers from the sidelines.

Inspiration from Steven Salmieri and his wife Sydney Michelle

Inspiration from artist, hat designer and jewelry maker Carol Markel

Inspiration from my husband Paul Levitt who is designing a book with Dana Martin about his visit with Man Ray

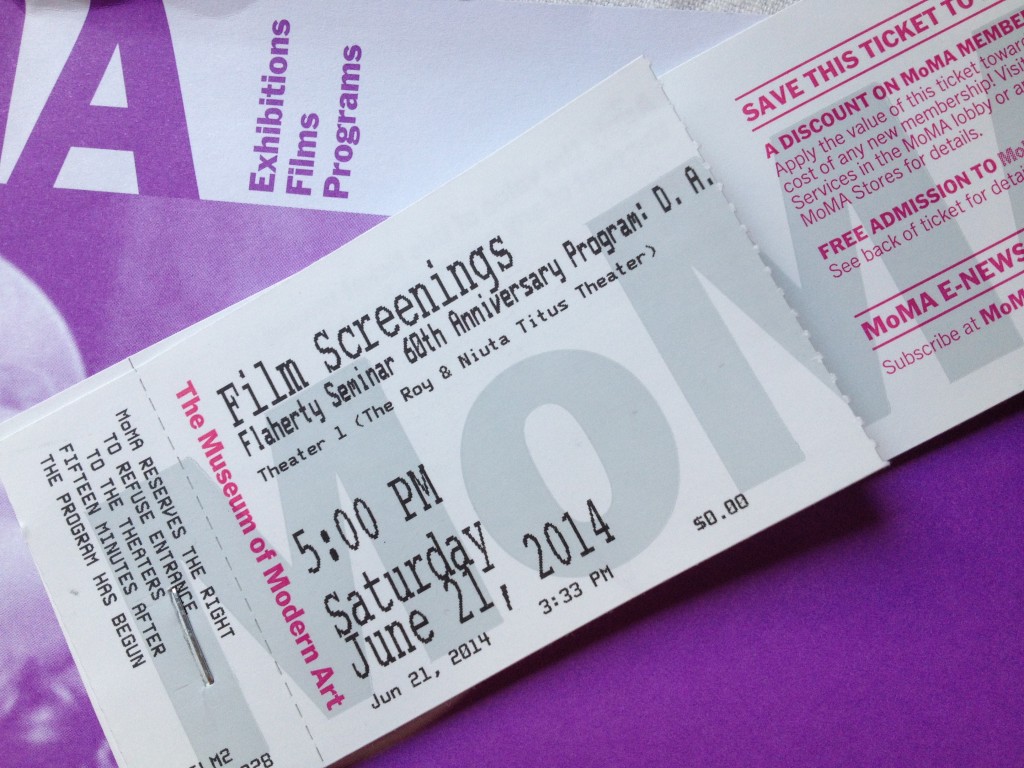

More inspiration from a screening and Q&A with D.A. Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus

Before my New York trip I got word that I received a fellowship to go to China to join a group of high school educators form Canada and New Jersey on a World War II centered study tour. It would be my first trip there, so China was on my mind.

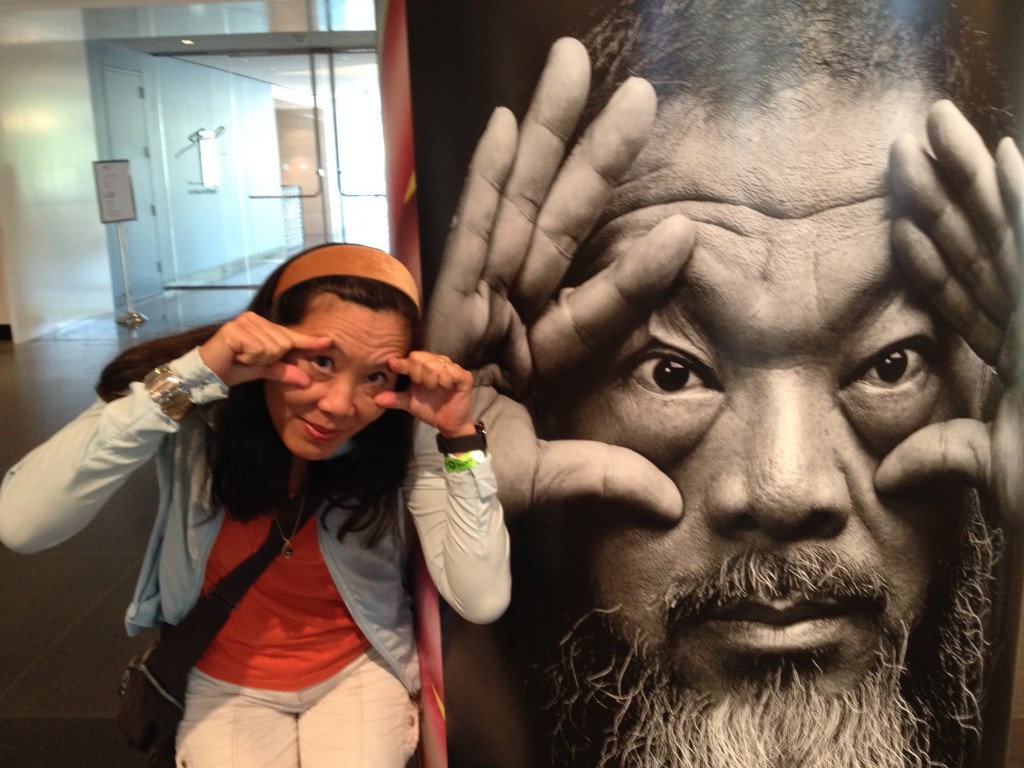

Looking ahead to China in July at the Ai Wei Wei exhibit in Brooklyn

Imagining China

China Kitsch

Li Ling-Ai’s spirit is also close at hand when I am in NYC. Her great friend Larry Wilson offered to point out the third floor apartment where she spent most of her life on West 55th street. The breeze picked up and the trees outside the apartment did a dance as we looked up to the third floor.

The Power of the Press, Part 2 — Roy Cummings

A blog in support of FINDING KUKAN’s 10K in 10weeks “Keep This Film Alive Campaign”.

How was the pioneering female reporter May Day Lo connected to KUKAN’s co-producer Li Ling-Ai? Leads to that question had dried up for me a long time ago. Then last November Honolulu Star-Advertiser reporter Mike Gordon wrote a big feature article about FINDING KUKAN. I received a number of enthusiastic emails about the article and one strange phone call.

“I’m so mad!” Those were the first words Susan Cummings said to me. “I’m sure he knew her. If only he were still here, he could tell you.” She was referring to her husband who was no longer alive. To tell you the truth, I thought Susan might be a raving lunatic. But as we talked longer I realized that Susan’s late husband was Roy Cummings. He’d been a reporter at the Honolulu Advertiser in 1937, the same year KUKAN’s director Rey Scott started working there. Like Rey Scott, he had roots in Missouri. Roy was also notable for trying to unionize the Advertiser at that time. Susan told me he was fired for doing so, was almost run over in a parking lot, and blackballed by the Honolulu Star-Bulletin too. It would take Roy Cummings another 12 years to establish the Hawaii Newspaper Guild in 1949. He seemed just like the kind of guy that Rey Scott would gravitate to.

Roy Cummings founded the Hawaii Newspaper Guild in 1949 (photo courtesy of Honolulu Star-Bulletin)

Coincidentally Roy’s first wife Margaret Kam had been a “person of interest” to me when I was trying to hunt down the real life inspirations for the detective Lily Wu. Because Margaret was a colorful character too – a Chinese actress and reporter in Hawaii who had the gumption to marry a white guy at a time when traditional Chinese families still frowned upon those things.

Margaret Kam (center) mans the all female copy desk at the Honolulu Star-Bulletin during WWII (courtesy Susan Cummings)

Once I made the connection, the conversation with Susan started sparking with names and situations from Roy Cummings’s past. I mentioned that I had been trying to find information on the Star Bulletin reporter May Day Lo, and Susan exclaimed, “May Day Lo was Roy’s first love!” It turns out that Roy and May Day went to journalism school together in Missouri. Roy fell in love with May Day and followed her out to Hawaii.

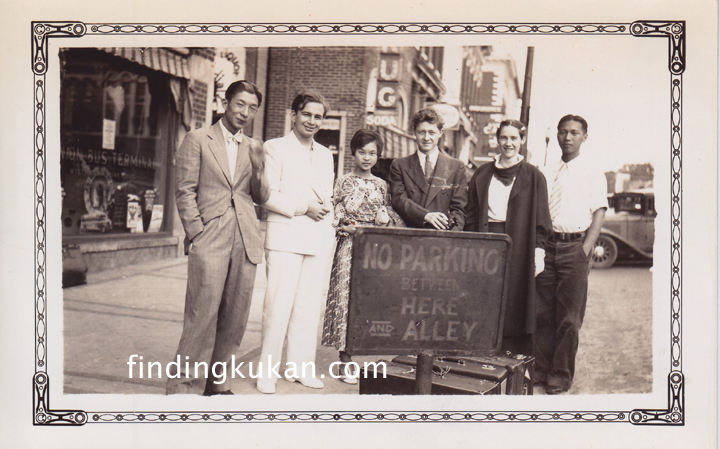

May Day Lo and Roy Cummings (center) gather with fellow University of Missouri journalism students in downtown Columbia

Now I was the one who was mad that Roy was no longer alive. I felt sure that he’d been acquainted with Li Ling-Ai and Rey Scott in one way or another. He probably could have provided some interesting stories about the two of them and the making of KUKAN. Susan graciously invited me over to her house in Lanikai to look at Roy’s photograph from the time period – the next best thing to meeting the man in person.

Susan Cummings with Wyeth portrait

Susan Cummings hunts for clues in her husband’s photo albums

Roy’s photos put more flesh and blood on what had previously been merely names on a page. They also gave me some insight into the lifestyle Rey Scott must have experienced when he first arrived here.

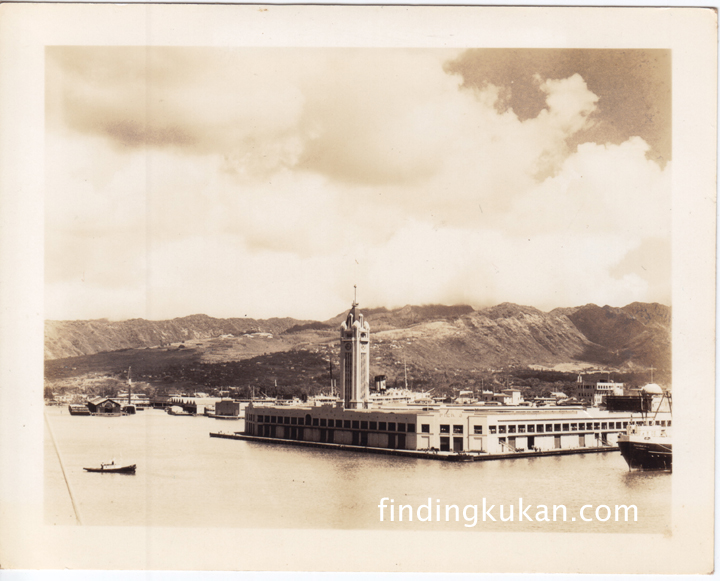

Aloha Tower in the mid 1930s (photo courtesy Susan Cummings)

Like Roy Cummings, Rey Scott holed up in Waikiki when he first got to Hawaii. Could his room have looked like this? (photo courtesy of Susan Cummings)

But the photos didn’t do much to fill in the gaps of the KUKAN story. In fact they brought up more questions than answers. Susan herself was mystified as to what happened between May Day Lo and Roy. Why had he married Margaret Kam instead of May Day? She’d never thought to ask Roy about it when he was alive. I wanted to know if anyone had saved May Day’s papers and if Ling-Ai’s letters or clues to KUKAN were amongst them.

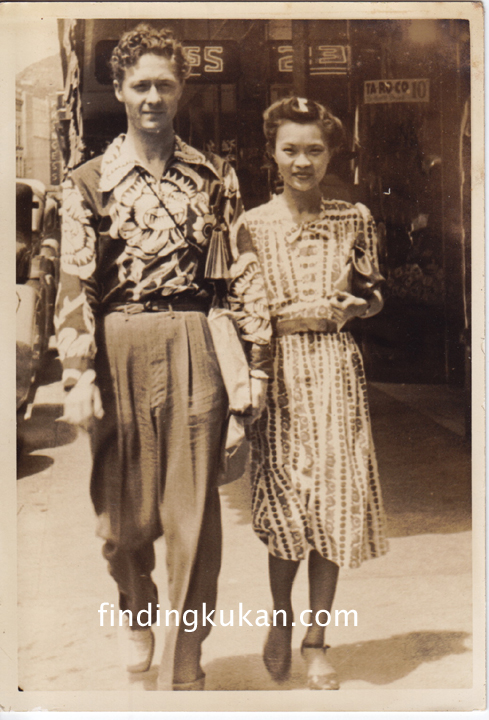

Roy Cummings and May Day Lo in downtown Honolulu (photo courtesy Susan Cummings)

Egged on by mutual curiosity Susan and I exchanged a flurry of emails and research findings in the next few weeks. Susan proved to be a willing and able sleuth, and together we found out some very interesting things which I’ll share in future posts. For now I want to pay tribute to the “father of the Hawaii Newspaper Guild” and thank the ghost of Roy Cummings for putting Susan and I together. Of course the “power of the press” had a lot to do with it too.

Support our 10K in 10 Weeks campaign by clicking the red button.

(As of 9/24/13 we have raised $7,165 and have $2,835 more to raise by 10/15/13)

Soo Yong – Another Chinese Woman We Should Know More About – Part 2

A blog in support of FINDING KUKAN’s 10K in 10weeks “Keep This Film Alive Campaign”.

A family story often told about Soo Yong (born Ahee Young) is that when she was four or five years old her father became gravely ill and summoned the family to hear his last words. But Ahee was missing. The family searched all over for her. They finally found her in Wailuku town. She was completely mesmerized by the performance of a Chinese opera troupe who had come to town. This is Soo Yong’s earliest dramatic memory.

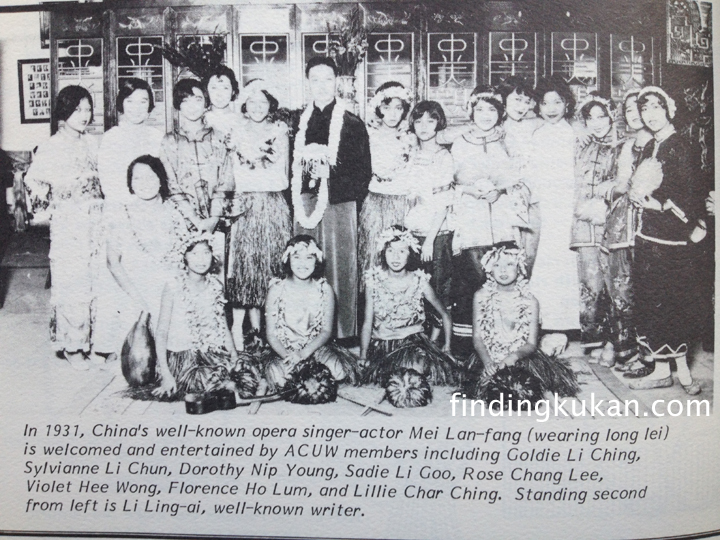

Chinese Opera Performers in Hawaii

Si it must have been a dream come true for Soo Yong when in 1930, at 28 years of age, she was chosen to accompany the most famous Chinese opera star of all time on a six-month tour of America.

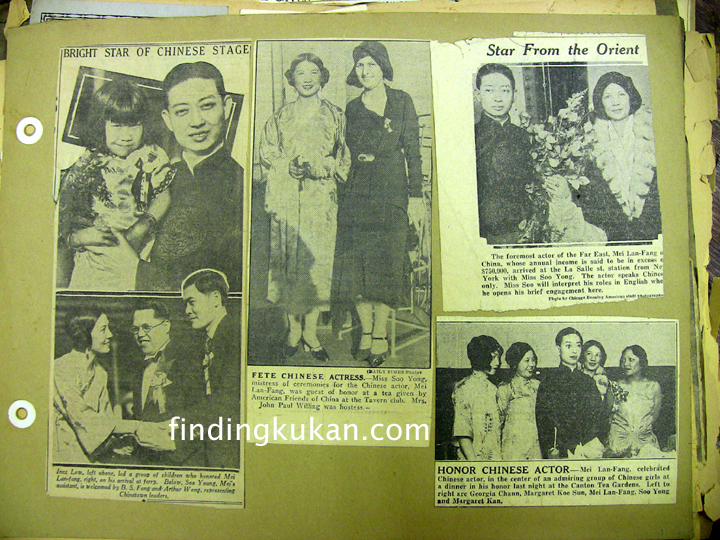

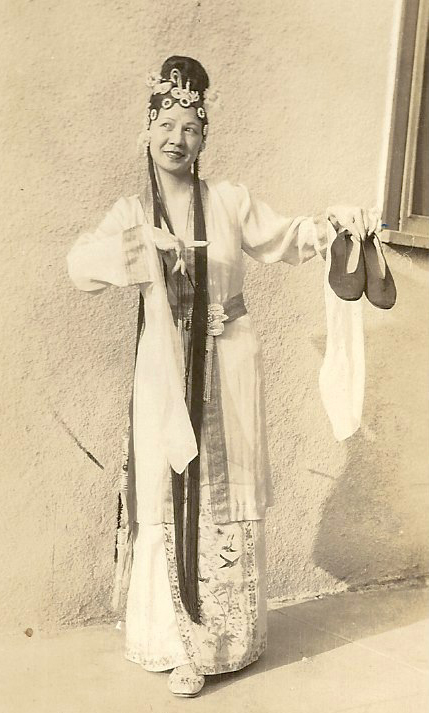

Soo Yong acts as Mistress of Ceremonies for Mei Lanfang’s 1930 tour of America

Mei Lanfang was also idolized by Li Ling-Ai whose dramatic interests were stirred up by Chinese opera performances her father took her to when she was a young girl. During his 1930 tour Mei stopped in Honolulu and Li Ling-Ai had a chance to meet him.

Photo from the ACUW publication TRADITIONS FOR LIVING

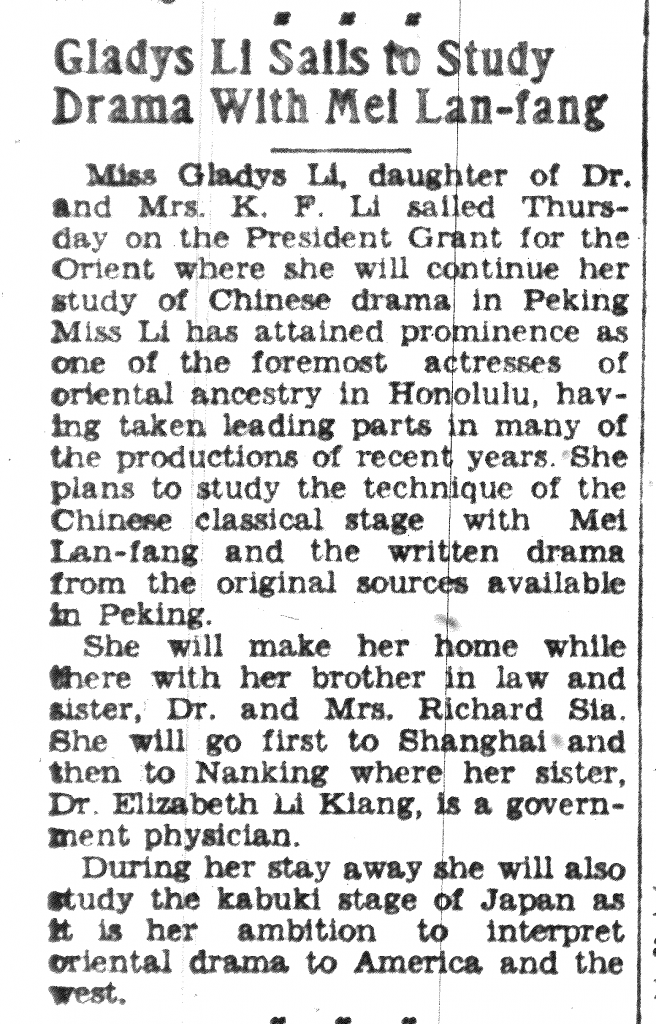

A year or so later Li Ling-Ai left on her second trip to China and told newspaper reporters she intended to study with the great man – a lofty goal for a recent graduate of the University of Hawaii. I wondered if Soo Yong’s insider position emboldened Li Ling-Ai to approach the great Mei for lessons.

Honolulu Star Bulletin Article from August 6, 1932

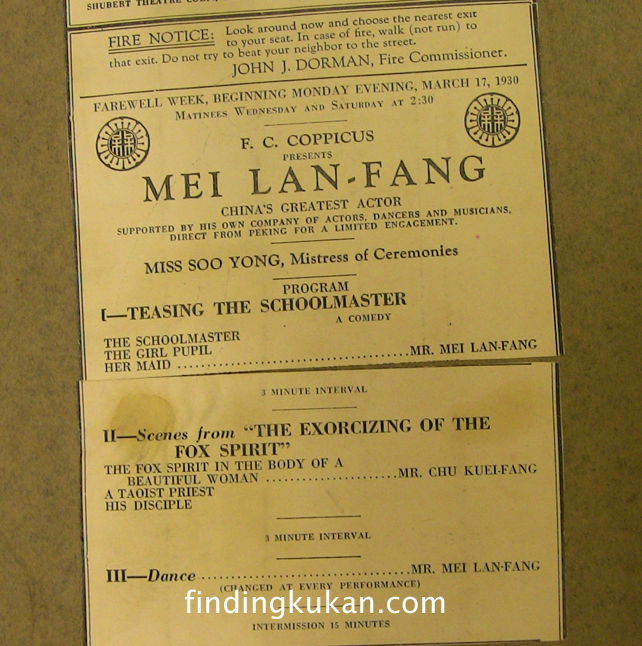

I found no subsequent mention of Li Ling-Ai studying with Mei Lanfang. But several biographies of Li state that she studied privately with the famous dancer Chu Kuei Fang. It was hard to find any mention of Chu Kuei Fang on the internet and I began to doubt Li Ling-Ai’s claims. But in Soo Yong’s personal scrapbook that was donated to the University of Hawaii, I discovered Chu listed as a performer in a 1930 program for Mei Lanfang’s tour.

Chu Kue-Fang performs on the same program as Mei Lanfang

Chu must have been very accomplished to share stage time with the great Mei Lanfang. I wonder if this old photo, found amongst Li Ling-Ai’s possessions, is of Chu Kuei Fang. If anyone can positively identify the man in the photo, please let me know.

Could the man behind Li Ling-Ai be Chu Kuei-Fang?

Soo Yong and Li Ling-Ai also shared a passion for helping their Chinese homeland during the Japanese invasion of the country. As early as 1937 Soo Yong was performing in benefits to aid Chinese refugees.

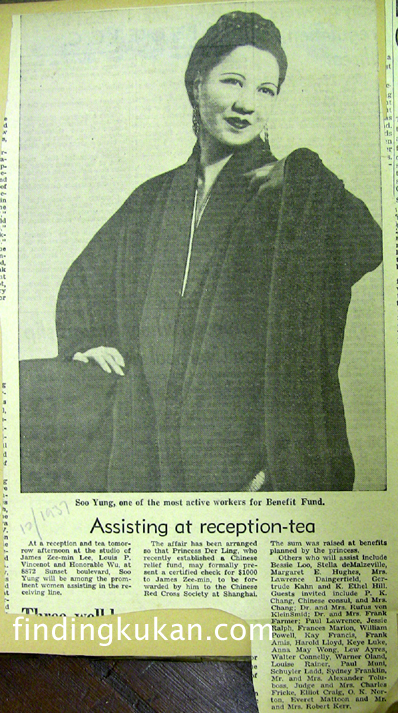

December 1937 Soo Yong hosts tea for China Relief

1937 was also the year that Li Ling-Ai sent Rey Scott to China so that the story of the people of China could be told in photographs and film – the film would eventually become KUKAN. Whether Soo Yong was a role model for Li Ling-Ai or simply another extraordinary Chinese woman who became a political activist when war came we might never know. But one thing’s for certain — we should definitely know more about her than we do.

Soo Yong: Another Chinese Woman We Should Know More About — Part I

Could the Chinese American actress Soo Yong have been an inspiration for the fictional Lily Wu? (photo courtesy of Barbara Wong)

I’m starting a 10-week blog-a-thon in support of our 10K in 10weeks “Keep This Film Alive Campaign”. The goal: get us back into the edit room on October 15 to finish a rough cut of FINDING KUKAN. What better way to kick off that effort than to re-visit my search for LILY WU – the fictional detective created by author Juanita Sheridan. According to Lily’s friend and Watson-like companion Janice Cameron, “Lily is a chameleon. She can change effortlessly into whatever character the occasion requires…” Lily is also smarter, sexier and more worldly than most of the Caucasian characters she runs into.

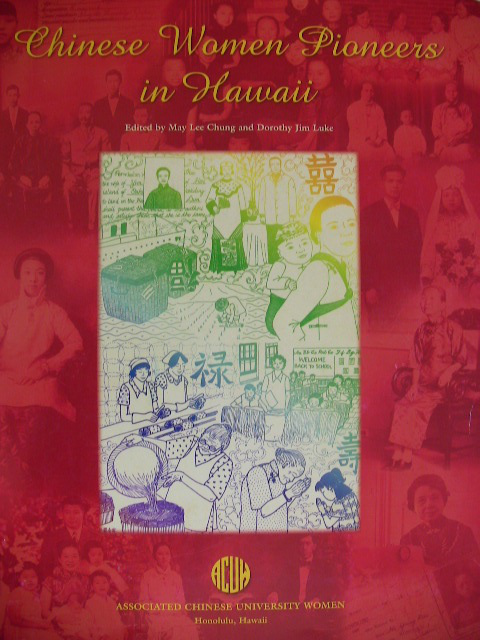

This book, published by the Associated Chinese University Women of Hawaii, is a wonderful collection of short bios

While trying to locate the real life inspirations for Lily Wu I recall poring over what I now think of as THE ORANGE BIBLE (see photo above) and stopping short at the entry for Soo Yong. Why? Because Soo Yong was a Chinese movie star from Hawaii! She appeared glamorous and gutsy, running away from a restrictive small town life in Wailuku, Maui for the more cosmopolitan Honolulu where she put herself through school at the University of Hawaii and then Columbia University in NYC. She was just the kind of woman who might have inspired Juanita Sheridan to create Lily Wu. But my interest in Soo Yong tailed off when I discovered that Soo Yong had left Hawaii before Juanita Sheridan arrived there, making it unlikely that the two women were friends.

My interest in Soo Yong was re-ignited when Li Ling-Ai’s sole surviving sister mentioned that Ling-Ai had spent time in Hollywood and had been friendly with a Chinese actress from Maui. Sure enough, a keyword search through the Los Angeles Times brought up a 1936 article placing Soo Yong and Li Ling-Ai together in Hollywood:

“East is east and west is west, and the two of them met last Tuesday afternoon at Joine Alderman’s Salon. The east was personified by a lovely Chinese lady whose name and voice are poetry itself, Li Ling Ai. Clad in her native black satin robes, embroidered in gold and silver and shining colors, she told the forty or so debs who comprise the salon about her native country. … And her words about the beauties of Pekin and her studies in ancient philosophy were translated to the debs by another Chinese-robed lady, Soo Yung.”

The gossip column inaccurately assumed that Ling-Ai could not speak English and Soo Yong was there merely as a translator, but it whetted my appetite to learn more about Soo Yong. Could she have been a mentor or role model for Li Ling-Ai?

Clark Gable and Soo Yong in The China Seas

Being an old movie nut, one of the first things I did was rent one of the Clark Gable movies Soo Yong had been in, China Seas. Although the movie depicts most Chinese in stereotypical coolie roles, Soo Yong convincingly plays a high-brow Chinese aristocrat who out-classes Gable’s ex-girlfriend played by Jean Harlow. This small 1935 role would lead to Yong playing two parts in the 1937 hit The Good Earth. She was also Jack Soo’s mother in Flower Drum Song and had supporting roles in Soldier of Fortune with Clark Gable, Peking Express with Joseph Cotton, and Love is a Many Splendored Thing with Jennifer Jones. Why we don’t know much about her may be because she was never able to have a full-fledged Hollywood movie career.

In 1935 Soo Yong advised islanders that Asians have “A Chinaman’s Chance” of breaking into Hollywood.

In the 1930s Soo Yong was interviewed by Loui Leong Hop for the Honolulu Star-Bulletin:

“When asked about the possibility for local-born orientals to break into the talkies, she simply said, “A Chinese has a Chinaman’s Chance.” Explaining further on this point Miss Young stated that at present the Hollywood studios are name crazed. If there’s a production which required an oriental to play the part, the Hollywood producers would invariably select one of their more famous actors or actresses.”

Unfortunately not much has changed in Hollywood, and Asians still struggle to find starring roles on the big screen.

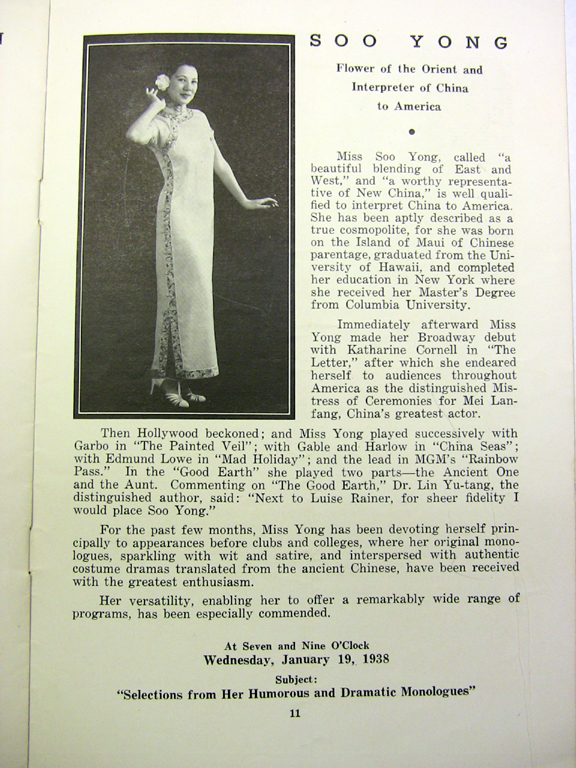

Soo Yong, Interpreter of China to America

Soo Yong would eventually make a living on the lecture circuit, performing entertaining Chinese monologues to educate audiences around the country about Chinese culture. As of this date Soo Yong does not even have a Wikipedia page, but we should definitely know more about this pioneering Chinese American actress. Stay tuned for part two of this blog where I’ll write about some amazing discoveries I found in Soo Yong’s personal scrapbook.

Support our 10K in 10 Weeks campaign by clicking the red button.